If one wants to claim something is accepted 'science", it should withstand the scrutiny of a peer reviewed, journal such as Lancet, NEJM, etc. Pretty charts in a political publication are not 'science'. Most scientific literature also avoids ascribing snarky negative motivations to those who disagree.

Colleges

- American Athletic

- Atlantic Coast

- Big 12

- Big East

- Big Ten

- Colonial

- Conference USA

- Independents (FBS)

- Junior College

- Mountain West

- Northeast

- Pac-12

- Patriot League

- Pioneer League

- Southeastern

- Sun Belt

- Army

- Charlotte

- East Carolina

- Florida Atlantic

- Memphis

- Navy

- North Texas

- Rice

- South Florida

- Temple

- Tulane

- Tulsa

- UAB

- UTSA

- Boston College

- California

- Clemson

- Duke

- Florida State

- Georgia Tech

- Louisville

- Miami (FL)

- North Carolina

- North Carolina State

- Pittsburgh

- Southern Methodist

- Stanford

- Syracuse

- Virginia

- Virginia Tech

- Wake Forest

- Arizona

- Arizona State

- Baylor

- Brigham Young

- Cincinnati

- Colorado

- Houston

- Iowa State

- Kansas

- Kansas State

- Oklahoma State

- TCU

- Texas Tech

- UCF

- Utah

- West Virginia

- Illinois

- Indiana

- Iowa

- Maryland

- Michigan

- Michigan State

- Minnesota

- Nebraska

- Northwestern

- Ohio State

- Oregon

- Penn State

- Purdue

- Rutgers

- UCLA

- USC

- Washington

- Wisconsin

High Schools

- Illinois HS Sports

- Indiana HS Sports

- Iowa HS Sports

- Kansas HS Sports

- Michigan HS Sports

- Minnesota HS Sports

- Missouri HS Sports

- Nebraska HS Sports

- Oklahoma HS Sports

- Texas HS Hoops

- Texas HS Sports

- Wisconsin HS Sports

- Cincinnati HS Sports

- Delaware

- Maryland HS Sports

- New Jersey HS Hoops

- New Jersey HS Sports

- NYC HS Hoops

- Ohio HS Sports

- Pennsylvania HS Sports

- Virginia HS Sports

- West Virginia HS Sports

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Making Covid permanent?

- Thread starter watu05

- Start date

If you’ve been following the mask mandates at all you would have seen it’s apparent they have no significant affect on transmission rates. After two years those “pretty charts” do in fact provide visual evidence of as much. Charts which are based on actual data btw. Are you still claiming that mask mandates were an effective measure which significantly decreased transmission rates in the areas which they were implemented ?If one wants to claim something is accepted 'science", it should withstand the scrutiny of a peer reviewed, journal such as Lancet, NEJM, etc. Pretty charts in a political publication are not 'science'. Most scientific literature also avoids ascribing snarky negative motivations to those who disagree.

Op Ed from NYTimes. What an effective Mask Mandate Might Look Like?

On Sunday, I spent nearly five hours on an airplane, flying home from the West Coast. For long stretches of the flight, whenever the crew was serving food and drinks, many passengers were not wearing masks. Even when people did have their masks on, many wore them below their noses.

My flight was the day before a federal judge threw out the C.D.C.’s transportation mask mandate, but my experience was typical, as any recent flier can attest. The mandate was already more of an aspiration than a reality, which indicates that the ruling may be less important than the furor over it suggests. The Covid-19 virus, after all, doesn’t take a break from spreading so that you can enjoy the in-flight beverage service.

As Michael Osterholm, a University of Minnesota epidemiologist, puts it, a mask mandate with as many exceptions as the airline mandate is like a submarine that closes three of its five doors.

On the other hand, research shows that, when used correctly, masks can be a valuable tool for reducing the spread of Covid. How, then, should the country be thinking about masks during the current stage of the pandemic? Today’s newsletter tries to answer that question.

Broad and lenient

The trouble with the transportation mask mandate was that it was both too broad and too lenient.

Its breadth required people to muzzle their faces for long periods of time, and most people don’t enjoy doing so. (If you doubt that, check out the gleeful responses of airline passengers and school children when told they didn’t have to wear masks anymore.)

A central lesson of public health is that people have a limited capacity to change their routine. They’re not machines. For that reason, the best responses to health crises depend on triage, with political leaders prioritizing the most valuable steps that people can take. Whenever politicians impose rules that are obviously ineffective, they undermine the credibility of the effective steps.

The transportation mandate had so many exceptions that many Americans understandably questioned its worth. Travelers took off their masks to eat and drink. Some flight attendants removed their masks to make announcements. Some passengers wore their masks on their chins. The mandate also did not require N95 and KN95 masks, which are more effective against the virus than cloth masks or standard medical masks.

These problems — the open doors on the mask-mandate submarine — help explain a pandemic conundrum: Rigorous laboratory tests show that masks reduce Covid transmission, but supporting real-world evidence tends to be much weaker.

The most glaring example in the U.S. is that liberal communities, where masks are a cherished symbol of solidarity, have experienced nearly as much Covid spread as conservative communities, where masks are a hated symbol of oppression. Another example is school mask mandates, which don’t seem to have had much effect. A third example is Hong Kong, where mask wearing is very popular (although often not with N95 or KN95 masks, Osterholm notes); Hong Kong has just endured a horrific Covid wave, among the world’s worst since the pandemic began.

Osterholm, who spent 15 years as Minnesota’s state epidemiologist and has advised both Democratic and Republican administrations in Washington, argues that much of the U.S. public health community has exaggerated the value of broad mask mandates. KN95 and N95 masks reduce the virus’s spread, he believes, but mandates like the one on airlines do little good.

“Public health advice has been way off the mark, all along, about mask protection,” he told me. “We have given the public a sense of a level of protection that is just not warranted.”

Narrow and strict

A more effective approach to mask mandates would probably be both narrower and stricter. It would close the big, obvious loopholes in any remaining mandates — but also limit the number of mandates.

The reality is that masks are less valuable today than they were a year or two ago. Covid vaccines are universally available in the U.S. for adults and teenagers, and the virus is overwhelmingly mild in children. Treatments for vulnerable people are increasingly available.

And consider this: About half of Americans have recently had the Omicron variant of Covid. They currently have little reason to wear a mask, for anybody’s sake.

Together, vaccines and treatments mean that the risks of severe Covid for boosted people — including the vulnerable — seem to be similar to the risks of severe influenza. The U.S., of course, does not mandate mask wearing every winter to reduce flu cases. No country does.

Another relevant factor is that one-way masking reduces Covid transmission. People who want to wear a mask because of an underlying health condition, a fear of long Covid or any other reason can do so. When they do, they deserve respect.

Still, if Covid illness begins surging again at some point, there may be situations in which mandates make sense. To be effective, any mandates probably need to be strict, realistic and enforced. Imagine, for example, that a subway system mandated KN95 or N95 masks inside train cars — but not on platforms, which tend to be airy.

Or imagine that the C.D.C. required high-quality masks in the airport and aboard a plane on the runway — but not in flight when people will inevitably eat and when a plane’s air-filtration system is on. “When I travel, I’m always more worried about in-airport exposures than I am the plane,” Jennifer Nuzzo, a Brown University epidemiologist, said.

Unfortunately, the U.S. has spent much of the past two years with the worst of all worlds on masks. People have been required to wear them for hours on end, causing frustration and exhaustion and exacerbating political polarization. Yet the rules have included enough exceptions to let Covid spread anyway. The burden of the mandates has been relatively high, while the benefits have been relatively low. It’s the opposite of what a successful public health campaign typically does.

On Sunday, I spent nearly five hours on an airplane, flying home from the West Coast. For long stretches of the flight, whenever the crew was serving food and drinks, many passengers were not wearing masks. Even when people did have their masks on, many wore them below their noses.

My flight was the day before a federal judge threw out the C.D.C.’s transportation mask mandate, but my experience was typical, as any recent flier can attest. The mandate was already more of an aspiration than a reality, which indicates that the ruling may be less important than the furor over it suggests. The Covid-19 virus, after all, doesn’t take a break from spreading so that you can enjoy the in-flight beverage service.

As Michael Osterholm, a University of Minnesota epidemiologist, puts it, a mask mandate with as many exceptions as the airline mandate is like a submarine that closes three of its five doors.

On the other hand, research shows that, when used correctly, masks can be a valuable tool for reducing the spread of Covid. How, then, should the country be thinking about masks during the current stage of the pandemic? Today’s newsletter tries to answer that question.

Broad and lenient

The trouble with the transportation mask mandate was that it was both too broad and too lenient.

Its breadth required people to muzzle their faces for long periods of time, and most people don’t enjoy doing so. (If you doubt that, check out the gleeful responses of airline passengers and school children when told they didn’t have to wear masks anymore.)

A central lesson of public health is that people have a limited capacity to change their routine. They’re not machines. For that reason, the best responses to health crises depend on triage, with political leaders prioritizing the most valuable steps that people can take. Whenever politicians impose rules that are obviously ineffective, they undermine the credibility of the effective steps.

The transportation mandate had so many exceptions that many Americans understandably questioned its worth. Travelers took off their masks to eat and drink. Some flight attendants removed their masks to make announcements. Some passengers wore their masks on their chins. The mandate also did not require N95 and KN95 masks, which are more effective against the virus than cloth masks or standard medical masks.

These problems — the open doors on the mask-mandate submarine — help explain a pandemic conundrum: Rigorous laboratory tests show that masks reduce Covid transmission, but supporting real-world evidence tends to be much weaker.

The most glaring example in the U.S. is that liberal communities, where masks are a cherished symbol of solidarity, have experienced nearly as much Covid spread as conservative communities, where masks are a hated symbol of oppression. Another example is school mask mandates, which don’t seem to have had much effect. A third example is Hong Kong, where mask wearing is very popular (although often not with N95 or KN95 masks, Osterholm notes); Hong Kong has just endured a horrific Covid wave, among the world’s worst since the pandemic began.

Osterholm, who spent 15 years as Minnesota’s state epidemiologist and has advised both Democratic and Republican administrations in Washington, argues that much of the U.S. public health community has exaggerated the value of broad mask mandates. KN95 and N95 masks reduce the virus’s spread, he believes, but mandates like the one on airlines do little good.

“Public health advice has been way off the mark, all along, about mask protection,” he told me. “We have given the public a sense of a level of protection that is just not warranted.”

Narrow and strict

A more effective approach to mask mandates would probably be both narrower and stricter. It would close the big, obvious loopholes in any remaining mandates — but also limit the number of mandates.

The reality is that masks are less valuable today than they were a year or two ago. Covid vaccines are universally available in the U.S. for adults and teenagers, and the virus is overwhelmingly mild in children. Treatments for vulnerable people are increasingly available.

And consider this: About half of Americans have recently had the Omicron variant of Covid. They currently have little reason to wear a mask, for anybody’s sake.

Together, vaccines and treatments mean that the risks of severe Covid for boosted people — including the vulnerable — seem to be similar to the risks of severe influenza. The U.S., of course, does not mandate mask wearing every winter to reduce flu cases. No country does.

Another relevant factor is that one-way masking reduces Covid transmission. People who want to wear a mask because of an underlying health condition, a fear of long Covid or any other reason can do so. When they do, they deserve respect.

Still, if Covid illness begins surging again at some point, there may be situations in which mandates make sense. To be effective, any mandates probably need to be strict, realistic and enforced. Imagine, for example, that a subway system mandated KN95 or N95 masks inside train cars — but not on platforms, which tend to be airy.

Or imagine that the C.D.C. required high-quality masks in the airport and aboard a plane on the runway — but not in flight when people will inevitably eat and when a plane’s air-filtration system is on. “When I travel, I’m always more worried about in-airport exposures than I am the plane,” Jennifer Nuzzo, a Brown University epidemiologist, said.

Unfortunately, the U.S. has spent much of the past two years with the worst of all worlds on masks. People have been required to wear them for hours on end, causing frustration and exhaustion and exacerbating political polarization. Yet the rules have included enough exceptions to let Covid spread anyway. The burden of the mandates has been relatively high, while the benefits have been relatively low. It’s the opposite of what a successful public health campaign typically does.

Happy to see it acknowledged that mask mandates have failed to slow the spread of Covid. The article even admits that communities with high mask usage have a similar transmission rate as communities with low usage rates. Same for schools. Welcome aboard to what some of us have known for well over a year.

Opinion | Covid Drugs Save Lives, but Americans Can’t Get Them (Published 2022)

Once again, a dysfunctional health care system has hindered our pandemic response.

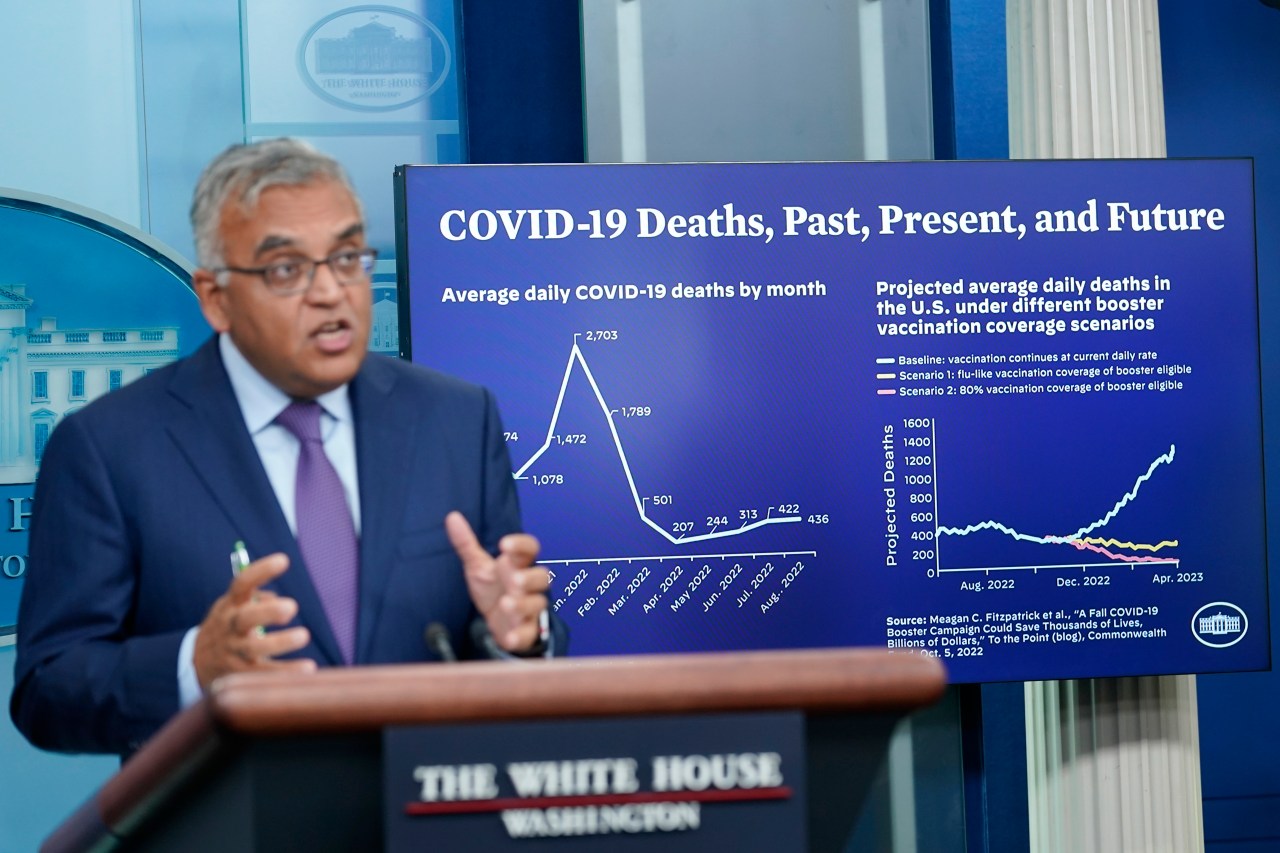

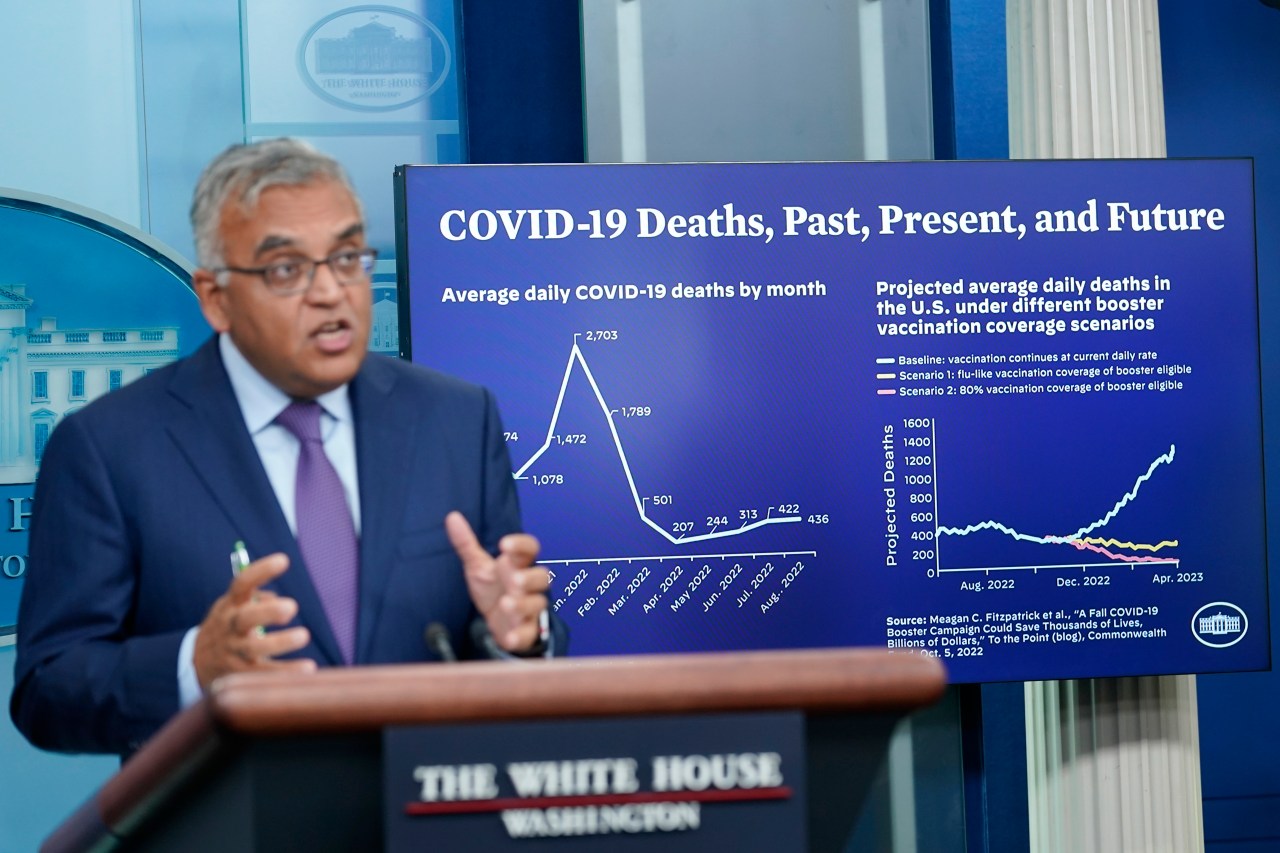

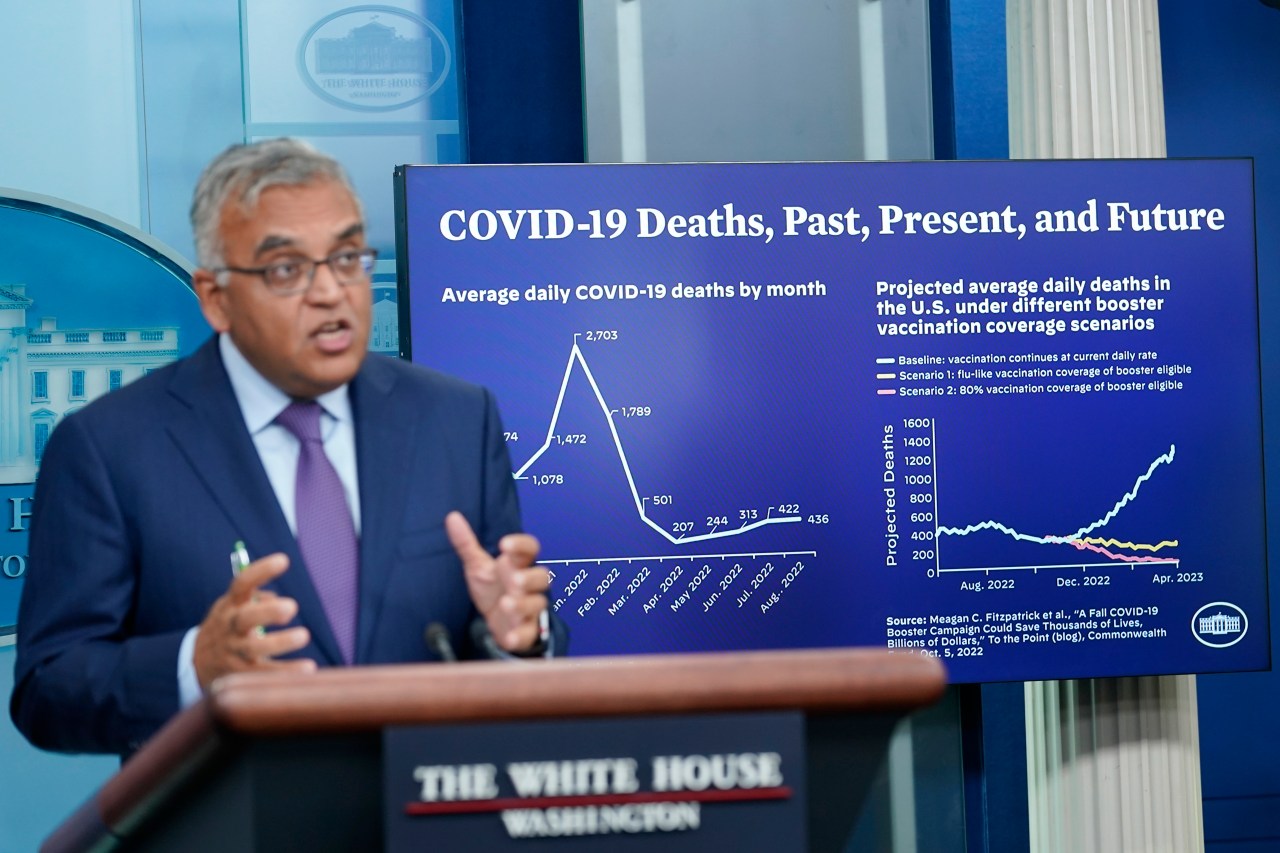

Yeah, I've been seeing stuff on these studies lately, and it sucks. You need to get a shot every two months just to be halfa$$ed covered. It's really needs to be once a month. That's a royal pain in the ass, and will get expensive. I wonder how often they will be paid for by the government. That's three times the cost at every two months. I'm hoping all these predictions of infections in the coming months are wrong. I'm just about up for my fourth shot at the end of the month. That means I would have to take four or five shots to get through the winter and protect my neighbor that I am taking care of. Ugh.

Yeah, I wouldn't doubt these studies are a little skewed to the right.(meaning more often, for decent protection, within the error correction norms) I'd like to know the +/-.Pfizer is making a killing off these vaccines/boosters. Almost $100B in revenue in 2021. Double that of 2020. Not a conspiracy guy but the current situation is one hell of a business model.

I have a feeling cdc gave a very broad estimate, with greater room for error, on possible infections in the coming months, and . If they had been more transparent on what studies were used I would feel more comfortable with their estimates.

The other remedies are for treating the illness after having contracted it, and are expensive. It is more likely the insurance companies that are acting prohibitively on them. Unless you are following the latest conspiracy theories, but that couldn't be true... Do you need some bleach or dewormer?the shots have a monopoly since the administration does not allow any other remedies

monochromal antibodies, ... and the gov could give them away free too.

oh by the way how many shots do I need?

boosters? how often? ... because Fauchi has the latest.

oh by the way how many shots do I need?

boosters? how often? ... because Fauchi has the latest.

As far as I know, those that are immunocompromised especially if they are over 65, get treated with monoclonal antibodies. That is if they catch it in time and can get in to the hospital with mild symptoms. If you already have severe symptoms and it is past so many days of catching it, the monoclonal antibodies aren't as effective.monochromal antibodies, ... and the gov could give them away free too.

oh by the way how many shots do I need?

boosters? how often? ... because Fauchi has the latest.

The government giving it away free comes out of your pocket, just like the vaccine. They pay the pharmaceutical companies. Insurance companies aren't covering it for people that aren't immunocompromised, but with people who are, they are paying for it as far as I know.

Next nonexistent problem you want to solve?...

according to the science, Fauchi, or wag?As far as I know, those that are immunocompromised especially if they are over 65, get treated with monoclonal antibodies. That is if they catch it in time and can get in to the hospital with mild symptoms. If you already have severe symptoms and it is past so many days of catching it, the monoclonal antibodies aren't as effective.

The government giving it away free comes out of your pocket, just like the vaccine. They pay the pharmaceutical companies. Insurance companies aren't covering it for people that aren't immunocompromised, but with people who are, they are paying for it as far as I know.

Next nonexistent problem you want to solve?...

Northshore Labs Tested Across Nevada. Its COVID Tests Didn’t Work.

www.propublica.org

www.propublica.org

The COVID Testing Company That Missed 96% of Cases

State and local officials across Nevada signed agreements with Northshore Clinical Labs, a COVID testing laboratory run by men with local political connections. There was only one problem: Its tests didn’t work.

Welcome to the Great Reinfection

A repeat encounter with Covid used to be a rarity. But now that Omicron has changed the game, expect reinfections to be the new normal.

He's been pandering for Fox News mentions lately.

Can someone explain to me why California is going back to mask mandates despite the scientific findings regarding the same?

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov

Correlation Between Mask Compliance and COVID-19 Outcomes in Europe - PubMed

Masking was the single most common non-pharmaceutical intervention in the course of the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. Most countries have implemented recommendations or mandates regarding the use of masks in public spaces. The aim of this short study was to analyse the...

Starting over again with new variants.

www.medpagetoday.com

www.medpagetoday.com

Opinion | Omicron BA.4 and BA.5: Starting From Scratch Yet Again

Here's what we know and what we still need to find out

Of course we are... we got a big election coming...Starting over again with new variants.

Opinion | Omicron BA.4 and BA.5: Starting From Scratch Yet Again

Here's what we know and what we still need to find outwww.medpagetoday.com

Yet another study showing mask mandates have no significant effect on transmission rates. Something some of us have known for the last two years.

www.sfgate.com

www.sfgate.com

Do mask mandates work? Bay Area data from June says no.

SFGATE compared Alameda County’s 7-day average case rate from the past two months to rates in neighboring Contra Costa, Santa Clara and San Francisco counties.

The new narrative. Could have fooled me. In El Paso even our hiking trails and parks were locked/wrapped in yellow tape. Is this like “real socialism has never been tried?”

Faucci's wet dream...

"The Pandemic is Over!" Joseph Robinnett Biden on 60 Minutes..

The White House contradicts the President .. say the Pandemic is still ongoing and have no plans to lift the Emergency Powers order...

The White House contradicts the President .. say the Pandemic is still ongoing and have no plans to lift the Emergency Powers order...

Joe “that’s what they wrote down for me to say”."The Pandemic is Over!" Joseph Robinnett Biden on 60 Minutes..

The White House contradicts the President .. say the Pandemic is still ongoing and have no plans to lift the Emergency Powers order...

There are several other

This is a promising approach that one of my friends with a career in biotech investing is watching closely.

The Administration doing everything in its power to fulfill WATU’s dream of making Covid permanent.

kdvr.com

kdvr.com

Biden administration extends COVID public health emergency

The Biden administration said Thursday that the COVID-19 public health emergency will continue through Jan. 11 as officials brace for a spike in cases this winter.

Just doesnt want to give up those emergency powers... didnt the ancient greeks call that a "tyrant"?The Administration doing everything in its power to fulfill WATU’s dream of making Covid permanent.

Biden administration extends COVID public health emergency

The Biden administration said Thursday that the COVID-19 public health emergency will continue through Jan. 11 as officials brace for a spike in cases this winter.kdvr.com

At least we're not Watu's homeland.The Administration doing everything in its power to fulfill WATU’s dream of making Covid permanent.

Biden administration extends COVID public health emergency

The Biden administration said Thursday that the COVID-19 public health emergency will continue through Jan. 11 as officials brace for a spike in cases this winter.kdvr.com

If we don't have any major spikes this winter, and he keeps extending it beyond the winter season, that's when he'll start getting into trouble over it. Especially when he is dealing with a Republican majority in one/or both houses.The Administration doing everything in its power to fulfill WATU’s dream of making Covid permanent.

Biden administration extends COVID public health emergency

The Biden administration said Thursday that the COVID-19 public health emergency will continue through Jan. 11 as officials brace for a spike in cases this winter.kdvr.com

What could possibly go wrong

www.foxnews.com

www.foxnews.com

Boston University researchers claim to have developed new, more lethal COVID strain in lab | Fox News

Researchers at Boston University added a spike protein from the Omicron variant with the original Wuhan strain, which has an 80% kill rate

I have a little more faith that our labs will not accidentally let it out. Research like that is important, in case something similar happens naturally.What could possibly go wrong

Boston University researchers claim to have developed new, more lethal COVID strain in lab | Fox News

Researchers at Boston University added a spike protein from the Omicron variant with the original Wuhan strain, which has an 80% kill ratewww.foxnews.com

Similar threads

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 938

- Replies

- 11

- Views

- 939

- Replies

- 17

- Views

- 926

Latest posts

-

-

-

-

-

📢 ALERT PLEASE READ -- Info on Rivals transition/combination with On3

- Latest: Bill Lowery